When a Lodz resident returned to his apartment in 1945 after the Germans fled the city, he found a pile of old papers in the kitchen by the stove, where previous tenants lit fires. Those people were no longer there because the apartment was located in the ghetto –– the wartime reality completely liquidated by the end of the summer of 1944.

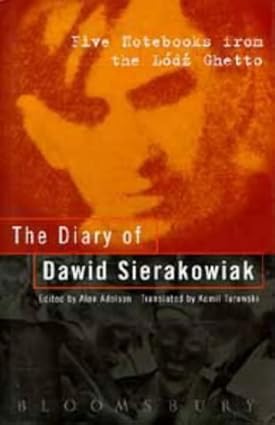

And in this pile of random papers, he found a handwritten diary that to this day is still one of the most moving documents describing German barbarism and their intentional extermination of the Jews. This manuscript that’d been published several times in Poland, was finally printed in English in 1996 as „The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak” and translated by Kamil Turowski for the Oxford University Press.

Essentially, „The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak” is the personal testimonial of an extremely sensitive, intelligent, and observant teenager, tenaciously writing down his ghetto experiences in real time. A first impression of his book echoes the famous words of the German writer, Erich Maria Remarque, „One death is a tragedy, a million –– a statistic.” Because the Lodz (Litzmannstadt) ghetto, the second largest in terms of population after the Warsaw ghetto, remains a mere statistic. Of the over 200,000 Jews who resided there (forcefully) between 1940 and 1944, most were exterminated under protocol, and of the last 70,000 or so who survived until liquidation, only a few remained after the war.

So this diary provides a description of an individual tragedy: the slow death of a 19-year-old’s ordinary Jewish family. As the author expressed the days and details of his life, he ultimately approached his own death, because by the summer of 1943 he finally passed away due to severe exhaustion, starvation, and tuberculosis that defined ghetto living conditions.

A constant and relentless hunger was an ever-present element of ghetto life. It killed anyone and everyone, including the strongest. Dawid frequently noted, „I was staggered today when I heard about the death of our former neighbor in the building, Mr. Kamusiewicz. I think his is the first death in the ghetto that has left me so deeply depressed. This man, an absolute athlete before the war, died of hunger here. His iron body did not suffer from any disease; it just grew thinner and thinner every day, and finally he fell asleep, not to wake again.”

Just like the Sierakowiak family, thousands died regularly. The ghetto was a perfectly designed mechanism that performed two key practical functions for Germany and its war effort: an economic necessity and the ideological purpose.

First and foremost, it was always a huge slave labor camp providing colossal war profiteering. Second, it was a practical machine for killing Jews –– the foundation and starting point for the Holocaust that consistently took place on the ground and in the war effort. The ghetto was essentially a factory for the “items” preeminently necessary for the German army orders, for the totalitarian government protocols, and for German private enterprise initiatives.

On the other hand, even just the food rations for ghetto inhabitants were so intentionally low that they effectively eliminated the weak, the debilitated, the hungry –– in other words, the useless. However, the system had a noticeable flaw, especially from the Nazi point of view; the flaw was the “imperfect and misaligned” human nature itself.

In other words, Jews in the ghetto –– as examples of human beings placed in subhuman conditions –– naturally and voluntarily shared their food with aged parents who were unable to work or their youngest children, by definition “unproductive” in a German industrial sense. And as a consequence, the productive part of the population –– the capable adult ghetto residents –– were constantly undernourished. The efficiency of their work suffered, and therefore the German war effort suffered.

The cost of living for these Jewish workers (food being their only form of payment) became too high for the Third Reich. In this situation, when potatoes and turnips were given to working people, but were actually eaten by non-working children and the elderly, far too much valuable German food was wasted. So unfortunately, the most “logical” Third Reich solution suggested itself to the ghetto administrators. In the summer of 1942, they simply decided to murder all the old people and all the children, perfectly combining economic necessity with an evil ideology.

That September Germans gassed nearly 20,000 children, the disabled and sick, and the elderly in mobile gas chambers in Chełmno.

The practical manifestation of the ghetto was always a corrupt, hierarchical creation, so it’s always been known that German orders to deport these specific groups rarely applied to the children and elderly parents of the ghetto elites and financial „aristocracy.” However, the numbers had to add up; the total number of victims had to match detailed German administrative statistics. Dawid Sierakowiak noted, „On this occasion, the Jewish police committed a kind of crime unknown before in the ghetto. The Germans demanded as a quota the number of sick registered on the hospitals’ lists. The police, as a result of various orders from influential people, wanted to spare the relatives of powerful persons, so they invented a new way of dealing with the situation: they went to the apartments of the sick who had already been driven out and, as if out of the blue, asked where the deported person was. When the unfortunate relatives answered that they had already been taken, the police took hostages anyway, unless the alleged fugitive was presented. As a result, when the Germans sent in vehicles today for the rest of the sick, a number of hostages were included to fill the quota, while the ‘connected’ ones stayed in hiding.”

But unfortunately the Germans always wanted more people. As many as possible. Each and every time. The Jewish administrators were forced to constantly release medical „commissions” to pick out the sick, those deemed “undeserving of life.” One of those victims was David’s healthy but “sickly-looking” mother: „My most Sacred, beloved, worn out, blessed, cherished Mother has fallen victim to the bloodthirsty German Nazi beast!!! And totally innocently, solely because of the evil hearts of two Czech Jews, the doctors who came to examine us.”

„The shabby old doctor who examined her searched and searched and was very surprised that he couldn’t find any disease in her. Nevertheless, he kept shaking his head, saying to his comrade in Czech: ‘Very weak, very weak.’ And despite the opposition and intervention from the police and nurses present at the examination, he added these two unfortunate words to our family’s record.”

The family did everything they could to save their mother, but to no avail. “I couldn’t muster the willpower to look through the window after her or to cry. I walked around, talked, and finally sat as though I had turned to stone. Every other moment, nervous spasms took hold of my heart, hands, mouth, and throat, so that I thought my heart was breaking. It didn’t break, though, and it let me eat, think, speak, and go to sleep.”

These Sierakowiak family deaths illustrate the regularity of ghetto dehumanization and the nefarious logic prevailing there. After the death of his mother, David’s father died of hunger, and David and his sister were left alone. And once David died, only his sister remained. Therefore, she became by far the most affected person in the family, yet there’s never a word about her horrible misery and final days in „The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak” because her brother, the author, perished before she did.

She was left all alone –– sixteen, sick, exhausted, starving. She probably survived another year in the ghetto (at most) and was murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau gas chamber in the summer of 1944. Even amid the horrors of every Holocaust murder, somehow to this day the idea of starving to death in one’s own bed in a ghetto apartment seems easier “to accept” than the planned, violent, collective extermination from poison chemicals in gas chambers.

When the Chełmno death camp had already ceased to operate, by the summer of 1944, when the war front was closing in, the last remaining ghetto inhabitants faced a long journey to Auschwitz-Birkenau. That’s where Germans murdered the last remaining ghetto Jews, including Dawid’s sister, Natalia Sierakowiak.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was also where the „king” of the ghetto, Chaim Rumkowski, was killed. In his last two years of administrative rule, his power and superiority dwindled, while Dawid Gertler and Aron Jakubowicz, who had better contacts with Germans, gained more influence. The Germans let them survive, Gertler dying in Germany in 1977 and Jakubowicz in the United States in 1981.

Dawid Sierakowiak noted this detail on December 29th, 1942: „Hunger is spreading in the ghetto, while the wealthy classes indulge themselves to the utmost. The higher ranking clerks in our office are organizing a real feed for themselves today. There will be vodka, soup, cakes, salad, and sausage! One can only try to imagine what the ‘real’ rulers will be having! Gertler’s gang, the market gardeners, the police, Kripo men, wagon drivers, Gestapo men, bakers — in one word, all those who gorge themselves from official and unofficial sources in the ghetto — they can all revel now.”

Sierakowiak’s diary began in the summer of 1939 and its author –– then only fifteen years old –– could never have known that his notes from a scout camp in the idyllic Polish mountains were a description of a world he’d never see again. Perhaps that’s why on Tuesday, July 18th, 1939, Dawid shared a terrified note with the words, „horrible news.”

He wrote, „A Jewish student from Poznan drowned today in the Dunajec. (They say he had a heart attack in the water, caused by exhaustion.)” Reading those words, knowing the future Dawid would endure, it’s almost impossible to refrain from a bitterly ironic thought –– that a Jew who drowned in a mountain river in the beautiful summer of 1939 at least avoided starvation in the ghetto or extermination in the gas chamber.

Just eighty years later, Dawid Sierakowiak’s diary provides us with a lasting, unique, and undeniable perspective of the ghetto. The majority of Jewish memoirs describing the Holocaust were only written well after the war, the authors by definition having become survivors. This caused their descriptions and remembrances to claim an obvious and unavoidable post-war perspective; the awareness of what happened to them after they survived and how their survival was received and recorded. In other words, the fact that they lived through the Holocaust gave their memoirs a distinct tone and tenor.

But Dawid Sierakowiak never knew what awaited him. He may have understood the imminent threat, but he refused to believe it. Or perhaps he refused to believe it for himself. (An undeniable human perspective.) Therefore, his reactions, observations, expectations –– his most essential hope for survival –– were recorded in all their authenticity because they were nothing more than the guarantee of another living moment. That was all for him, that was his everything.

That’s exactly why diaries can be so much more authentic and true, because they’re chronicles of what “is” as opposed to testimonials of what “was” like memoirs or editorials. And because there were relatively few „on-the-fly” records from the Holocaust in real time, Sierakowiak’s narrative is priceless.

For most people struggling to survive, writing a diary was hardly a priority. It was either pointless or difficult or far too dangerous. But for someone like Sierakowiak –– an intellectual with an artist’s soul and natural literary skills –– it became a form of escape from the reality of the ghetto nightmare.

He observed the world around him, the world he endured, as if rubbing his eyes and not believing that what he saw was his actual reality. At first he truly believed that war was impossible, and when it began, he insisted that Poland couldn’t be defeated. An excellent student awarded scholarships and fluent in five languages, he recalled that reading Thomas Mann’s “Buddenbrooks” in German emphasized the ideals of humanism and reinforced the faith in European culture.

And yet this very individual would soon experience unimaginable shock and disappointment when exposed to German primitivism –– pure evil and intentional cruelty –– in the context of a wartime demoralization of the Jewish elite in the ghetto. The daily notes and mementos kept by this boy reveal German barbarism directly and indisputably, as if under a microscope, because it was based on an individual: one family, one group of close friends, whose world utterly collapsed.

Especially young people –– those with hope and innocence just like Sierakowiak –– continually believed they must be living in a horrible dream. Day after day, they awaited news of Germany’s defeat; at least signs of it. Like any 18-year-old with their entire life ahead of them, they believed that „everything will be fine,” that they’re immortal, that everything will inevitably “work out.”

Unfortunately, the horrific reality surrounding them day after day proved their naivety. They simply couldn’t seriously accept the thought that most of them would perish; that whether due to starvation, disease, execution, or extermination, they weren’t going to survive. Dawid Sierakowiak noted wholeheartedly, „A few friends and I spoke a lot today about the future, and we have come to the conclusion that if we survive the ghetto, we’ll certainly experience a richness of life that we wouldn’t have appreciated otherwise. May the moment of liberation come at last!”

However the world these young people imagined and believed in was false. Among its many tenets, perhaps the most significant aspect of Sierakowiak’s diary is that it essentially became a description of the disintegration of illusions. That this world was neither just nor good, neither governed by law nor morality, but only cruelty, violence, and exploitation.

The sad fact is that Sierakowiak’s diary revealed the true nature of our world, our universal human experience, common to all slaves, all prisoners, all innocents throughout history. Whether we’re willing to accept it or not, the history of humanity is –– with the exception of brief bright moments –– a history of slavery.

And like the thousands of slaves around him –– in the ghetto, in occupied Poland, in Europe, and in the world –– Dawid Sierakowiak slowly faded away “into” himself. Hunger, physical weakness, and fever plunged him into infinite, inescapable darkness. His diary ended with these words: „In the evening I had to prepare food and cook supper, which exhausted me totally. In politics there’s absolutely nothing new. Again, out of impatience I feel myself beginning to fall into melancholy… There is really no way out of this for us.”

All that was left of Dawid Sierakowiak was his diary. His family, dear friends, and fellow ghetto inhabitants were all killed. And those who may have remembered “someone” named Dawid Sierakowiak ultimately forgot.

The only proof of his existence was a single, blurry photograph of his face in a school group photo. (When ghettos still had schools early on.) Dawid admired his photo, „I got the picture that we took of ourselves on the last day of school. It’s very pretty. I came out excellently in it.”

The only thing that transformed the memory of Dawid into a blessing for humanity was a Polish man who found papers in his apartment after the war. (And didn’t throw them out indiscriminately.)

That single moment in human history preserved a manuscript that proved his presence in the world. Were it not for that decision, Dawid’s words, his reactions, his experience, his very existence would never be known, remembered, or honored.

As mentioned earlier, human history is a dark story of unrelenting sin and slavery, but there are “exceptions.”

Let today’s article –– Dawid Sierakowiak’s story –– forever remain one of those “brief bright moments.”

Paweł Jędrzejewski