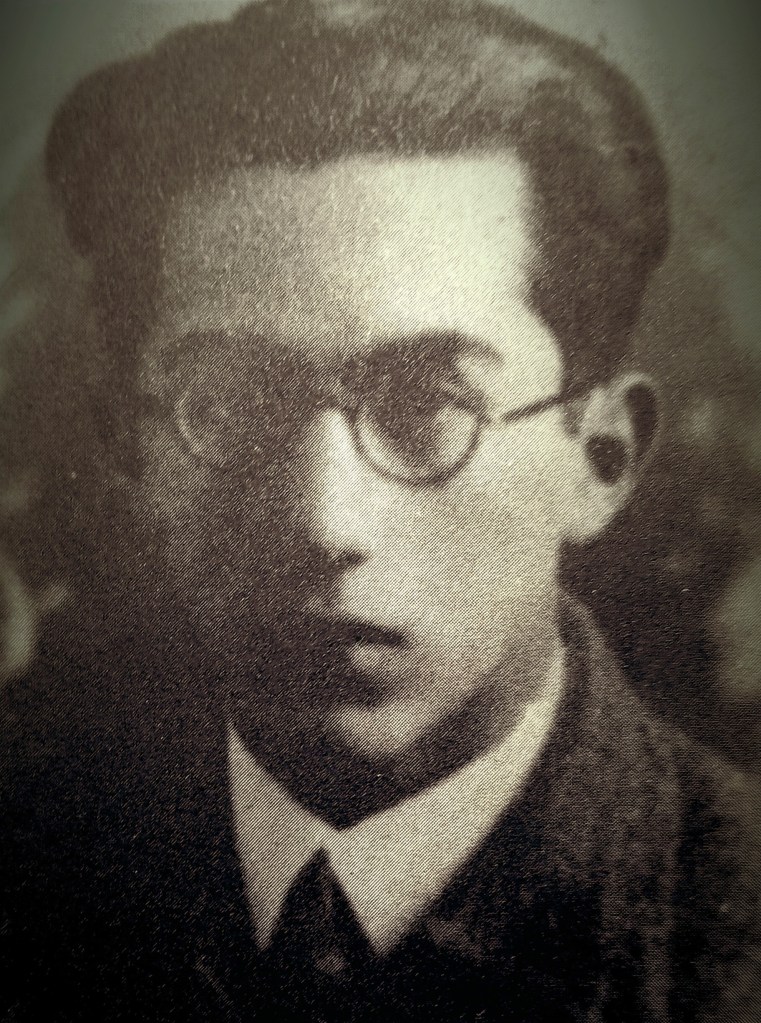

Calel Perechodnik

Today I’d like to remind us of a diary –– or rather a profound testament –– that was first published exactly thirty one years ago, or half a century after it was written. Undoubtedly, it’s one of the most distinct, truthful, and shocking publications from the Holocaust era.

Calel Perechodnik, the author and 27-year-old Polish Jew who knew only too well that he’d soon be murdered, spoke the harrowing truth: „A day will come when they will take me into a field, command me to dig a grave –– for me alone –– order me to remove my clothing and lie there on the bottom, and kill me quickly with a pistol shot to my head.”

The writer himself was an intellectual, an agronomist by education. He graduated in France and by the outbreak of World War II was financially well-off and entirely assimilated into Polish society. Yet as a resident of Otwock, a small town near Warsaw, by December 1940 he was just another one of the countless Jews the Germans locked in a ghetto. Perechodnik admitted, „In February 1941, seeing that war was not coming to an end and in order to be free from the roundup for labor camps, I entered the ranks of the Ghetto Polizei.”

In that one decision –– voluntarily joining the Jewish ghetto police –– the author didn’t realize that he’d signed a contract with the devil. The Jewish police became a tool in the hands of the Germans, implicitly and effectively facilitating the pursuit of their primary goal: the murder of all inhabitants of the ghetto. And it happened in every single ghetto in occupied Poland.

In 1942, the Germans began „Operation Reinhard,” where they murdered hundreds of thousands of Jews, aiming for nothing but total destruction. In August that year, they carried out the liquidation of the ghetto in Otwock. And under Nazi supervision, the Jewish police herded 8,000 Jews into the square near the railway station, all of them taken to the death camp in Treblinka and murdered in the gas chambers over the next few hours.

Perechodnik knew this, and most of the Jews in the ghetto knew it. The first escapees from the camp reached the Warsaw ghetto just a few days prior and shared what awaited the Jews. News spread fast, the ghetto population panicked. So under the supervision of auxiliary units in the German service consisting mostly of Soviet prisoners of war trained to murder civilians, the Jewish police went into immediate action.

With the intentional cooperation of the head of the Jewish police, the Germans staged protocols actively and explicitly. Jewish policemen didn’t hide their wives and children in cellars, but brought them to the square, where according to “guaranteed” promises, only there would they be officially released. And for those essential promises, the Jewish policemen herded remaining Jews into wagons without resistance.

„The policemen lead their own fathers and mothers to the cattle cars; themselves close the door with a bolt –– just as if they were nailing the coffins with their own hands. One policeman hands his father poison, and seeing this, his brother, a handsome sixteen-year-old, shouts and weeps, ‘Zygmunt, Zygmunt, and for me?’” Those policemen loaded thousands of people into train cars that day to save their wives and children. (And their own lives.)

However, the German promises regarding survival changed as the chaos ensued. The policemen’s wives were supposed to live, yet at that moment they left with everyone else. “‘Oh, great God, here we are, one hundred men, men for men, and before us are a few gendarmes with rifles. Boys! Let’s attack them; we’ll die together!’ –– I think to myself. But nothing comes of it.”

There was one exception. The author’s friend and police partner refused to leave his wife and son: „The policeman Abram Willendorf now makes clear the situation with his behavior. He says nothing to his wife; silently removes and throws aside his armband, hat, and number; and calmly sits on the ground. We are going away together, such is the silent answer of Willendorf, an honorable man.”

Perechodnik’s own wife asked for poison, which she’d willingly administer to the child and swallow herself. He recalled: „Eventually, I hear her voice. ‚Calek, try to get poison for me and the child’. My sister, Rachel, is asking me for the same thing. Where can I get poison? I am like a robot who can carry out a command but does not know what is going on around him. Finally, I go to the police station to telephone the Podolski pharmacy. How strange my words sound over the telephone. ‚This is Perechodnik speaking. I would like poison for three people, and please send it to the fenced-in area near the Police Station.'”

Finally, when all those destined for death were loaded in train cars and only policemen’s wives remained in the square, the “promise” was of course broken. „Suddenly we see that the Germans are pointing their guns at us. A command is heard. ‚All policemen to the side of the square on the double march! In two lines!’ It seems to us that we are standing in one place, but no, our legs, in spite of our will, carry us to the other side of the square. The German Satan reveals his true features. Now there is no longer any point in playing the comedy. (…) Our dear ones are going away into the dark night without farewells. From the distance I see only a cloud of dust and silhouettes that I cannot distinguish. All has been lost. Hurry now, policemen –– you executioners of your own wives and brothers –– render them their last turn; give them some bread through the windows of the wagons. Let no one say that the Germans begrudge Jews some bread. A long whistle –– ‘Anka, you have started off on your last journey. God, have mercy on me!’”

Am I a murderer? It’s the question the author asked, the question that haunted him the rest of his life.

So much so that it ultimately became the title of his memoir, his testament. Perechodnik gave his diary manuscripts to a Polish friend for safekeeping. After the war, it was handed over to the author’s brother, who survived in Russia. „Am I a Murderer?” was published in Poland in 1993 and in the United States two years later. In 2004, an extended version titled “Confession” was published in Poland. Perechodnik’s memoirs contain not only a description of the liquidation of the Otwock ghetto, but also the fate of the author’s family afterwards. The diary is extremely emotional –– a cry of seemingly deserved despair –– but it also embodies deep, insightful articulations of the indescribable death throes in which the Jews found themselves.

To imply that the world the author describes is “inhuman” is a profound understatement. When his aunt hid in a basement with her nine-year-old son, Perechodnik wondered what he could even do. „I brought food to them regularly. However, I lived in constant fear that gendarmes would track them down. (…) I advised her to poison her son and go on her own to Warsaw, where she could live and find work as a Polish woman.”

The world in Perechodnik’s memoir is a nightmare. An actual nightmare because it was real. Germans are murderers, robbers, sadists. Poles use the death of Jews to enrich themselves by taking over what the Germans didn’t steal or confiscate. Jews are disloyal to themselves, to each other, to everyone else, so as Perechodnik dismissively, even sneeringly writes, the myopic cowards do anything to survive an extra hour:

„You were passive, resigned, silent. Jews thought about everything, but not that they are descendants of Judah Maccabee. Where is your spirit that would have sounded with a thundering voice, ‘Let me perish, but together with my enemies!’ Before you are scarcely two hundred men with rifles, and you are eight thousand and have nothing to lose. Stand up, all of you together, shout one cry, and you will be free in a second. The Jewish nation is cursed, it is old, it has no strength to fight its opponents.”

But notedly, Perechodnik also directs these accusations against himself, fully aware of his guilt and understandably cursed by its implications. He blames himself as much as others. The nightmare reality required heroism from him, but only exceptionals were ever willing. Everyone knew being a decent person meant instant death, which is why most people chose to be passive. But ever so often there were heroes, extremely rare but real nonetheless.

As thousands waited in the square to be taken to gas chambers, „A young, comely, elegantly dressed woman approaches from the Polish neighborhood. We ourselves don’t know if she is Polish or Jewish. The German officers ask her politely what she wishes. In reply they hear that she is Jewish and wants to go with her mother, who is in the square. They are surprised and ask her several times, ‘Polen oder Jude?’ For the longest time they cannot understand. When they finally realize what this is all about, they don’t even bow their heads before such a sacrifice. She is beaten with clubs and pushed into the line.”

In evaluations of “Am I a Murderer?” most writers have overlooked the fact that the “brave and noble people” in these stories are almost exclusively Poles. While Perechodnik perceived them primarily as a nation entirely dominated by greedy, brutal blackmailers and thieves who robbed Jews and exposed them in the streets, it ended up being Poles who were the only ones who could be trusted, proving the slightest silver lining in humanity’s fallen state.

And fittingly, Perechodnik described ample cases. After all, it’s with Poles that he and his family hid after escaping from the ghetto, not to mention Buchalter’s family and other Jews. The sister of a Pole, with whom Perechodnik hid his diary, volunteered to take care of his 2-year-old daughter, but he never managed to actualize that care because he asked for help too late. Two „Brothers M” whom Perechodnik called „pre-war anti-Semites” underwent such an exemplary transformation through their association with Catholicism and the religious community that the author felt compelled to share: „The human hearts of the brothers protested against the extermination of Jews. The brothers, as much as possible, saved their friends and those they did not know. I bow in honor to them.”

There are similar attitudes described in Perechodnik’s story: individual “renegade” Polish policemen, a conscientious tram conductor, a random „elegantly dressed” Pole who offered Buchalter’s sister money and handed her food on the street. Of course these human beings are exceptions during a war, but in an inhuman world ruled by greed, cruelty, betrayal, and the dehumanization of the Jewish people, these attitudes are purposeful and profound.

They are the righteous who save the world. So we come to the crux…

Was Perechodnik a murderer?

First and foremost, he was just an ordinary human being who could’ve lived his life like anyone else if not for these inhuman circumstances, namely the explicit decision of the German state –– and the Nazis who ruled it –– that every Jewish man, woman, and child must be, and will be, murdered. There were never exceptions to this ideology, decision, and purpose.

When murder is committed, we’re subconsciously trained to view victims on one side and perpetrators on the other. But “Am I a Murderer?” dismantles that binary division. Entirely and conclusively.

Calel Perechodnik is a victim of genocide just as much as a participant in it. Although he himself never murdered anyone, he actively led human beings to where they would be murdered. The German “mission” to exterminate the Jews, which at the time seemed absolutely unimaginable to all but its creators, was to a large extent successful precisely because of the intentional destruction of this abstract division.

First, the Germans wanted the Jews to kill themselves in any way they could for as long as they could without ever even realizing it. The Judenräte in ghettos, the Jewish police, the Jews building gas chambers, the Jewish barbers cutting women’s hair before being gassed, the Jewish prisoners in the Sonderkommando directing a stream of people to the chambers and then removing the corpses of the murdered from them, finally burying them or burning them in crematoria and sorting the looted gold, money, and jewelry –– these are all elements of the practical extermination “mechanics” supposedly working on the principle of perpetual motion.

Second, there were two specific psychological factors that ensured the smooth operation of these mechanics, of this collective system designed to configure the logistics of a genocide. There was natural terror, ever-present and never-ending. „If I put up any resistance, I’ll die instantly.” And there was hope, the constant reminder that everyone around me is dying, but I’m still alive, so maybe I’ll survive, especially by being obedient, but more importantly, useful to the Germans.

And Perechodnik himself, a particularly astute observer, described this mechanism in detail, fully aware of how Jews were used by the Germans to murder their own people. But there is one more mental state, a “final” level of consciousness most desired by the Germans: utter hopelessness and total resignation. To put it simply, the realization that nothing matters anymore and death is the only escape. The ideal situation from the point of view of the German executioners is when the Jews volunteer to die:

„I remember the death of Mokotowska and her sister-in-law. (…) The day before their execution, these young, beautiful women sat calmly in front of the police station and talked to the policemen, who, after all, had known them for many years. I stopped by them (…) and asked why they didn’t run away (…) ‘Eee, there,’ they answered, ‘We don’t have any money. We’re in summer dresses; wherever we will go, the gendarmes will come.’ (…) The following morning, when the execution was coming to an end (…) I saw the two Mokotowski girls. Holding hands, they were marching in the direction of the place of execution. ‘Girls,’ I asked with a shaking voice, ‘You, too?’ (…) They walked faster. The last fifty feet they began to run. They ran to the embankment, kissed each other almost in flight, and threw themselves on the ground, still holding hands. Aim! Fire! Brains scattered, their hands clenched in their last convulsions. Not being able to separate them, the workers threw both bodies together into the pit.”

It was fear and hope that made Perechodnik lead his very own wife and child to the wagon going to Treblinka at the price of surviving that day. At that moment, he was deceived by the Germans. However, there were situations when the decision to free a human being he was leading to death depended entirely on him, on his decision, on his choice of what should be done versus what could be done.

For example, one time the gendarmes ordered him to bring an unknown Jewish woman to the police station, where she’d be shot. The woman begged him to let her go. Perechodnik refused because they were being watched by policemen. „The woman gets hysterical, starts to struggle, curses and cries that I will be responsible for her death. (…) To this day I hear her curses. Did I deserve this or not? My conscience tells me yes.”

Despite unimaginable and indescribable nightmares, our conscience rarely lets us go.

Calel Perechodnik lived until the autumn of 1944 thanks almost entirely to the help of Poles. He took part in the Warsaw Uprising that summer, the circumstances of his death remain unknown to this day.

One version claims he committed suicide; another figures he was burned alive while hiding from the Germans in a bunker.

Despite his death –– voluntary or passive, exceptional or unnoticeable –– Perechodnik’s stories, descriptions, and struggles live on thanks entirely to his diary.

And so does his timeless question. It will be asked over and over, garnering varied opinions and arguments and impressions, because by definition it is a question that can never be answered.

Paweł Jędrzejewski